Brought to you by Andrew Tickell

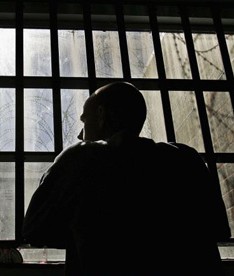

Rhubarb, rhubarb. Another defeat for the United Kingdom in Strasbourg yesterday. In James, Wells and Lee v. the United Kingdom, a chamber of the Court’s Fourth Section held that indeterminate sentences of imprisonment for public protection infringed Article 5 of the Convention. At his first Justice Questions in the House of Commons yesterday, our fresh-minted Conservative Lord Chancellor and Justice Secretary, Chris Grayling, advised MPs that:

“I’m very disappointed with the ECHR decision this morning. I have to say, it is not an area where I welcome the Court, seeking to make rulings. It is something we intend to appeal.”

One wonders which areas Mr Grayling would welcome the Court’s jurisdiction, but all in all, a somewhat tepid response from a man whose appointment was greeted by the Daily Mail with the enthusiastic suggestion that Grayling…

“… unlike his predecessor Ken Clarke, will have no truck with the cardboard judges at the European Court of Human Rights.”

Although the issue of indeterminate sentences has less political spice – say – than the right of prisoners to vote, no doubt we’ll soon discover that any adverse judgment provides a nice opportunity to re-intone the now familiar, largely mythic, belief that the injudicious “Euro” busybodies in Strasbourg are unduly “interventionist”, and over-disposed to upend domestic determinations, and make contrary decisions against the United Kingdom.

In anticipation, and out of curiosity, I dipped back into the official statistics to see where the United Kingdom sits comparatively. Is there any substance at all to the view that the European Court takes a more than typical interest in British applicants, entertaining more of their cases, and so making a greater number of contrary findings against the UK? Or, as the Mail put it a while back, is there any proof whatever that the Court is making “War on British Justice”?

What the figures say

A quick look at the institution’s official figures illuminates all this for moonshine and fantasy. As I outlined back at the beginning of the year, claims that the Court is engaged in a hyperactive, hostile review of UK laws conveniently ignores the fact that 97% of applications made against the United Kingdom are rejected as inadmissible, the vast majority without being communicated to the state for any sort of response. To put it another way, whether ministers are conscious of them or not, and although they will never enter the annals of the law reports, or appear on HUDOC, the UK government “wins” the vast, vast majority of cases lodged against it.

But what about those cases which do generate judgments from Strasbourg, like James, Wells and Lee? Is there a crumb of evidence that the United Kingdom is especially liable to be found in violation of the Convention?

Entertainingly, the evidence points in precisely the other direction, and one finds that between 1959 and 2011, the UK actually enjoyed one of the lowest rates of adverse judgments from the Court of all member states, only surpassed by the Netherlands, Andorra, Sweden and Denmark. Usually, this information is presented alphabetically by member state, but I’ve muddled things up a bit to allow an easier comparative perspective. Instead, I’ve ranked states by their rate of defeat in Strasbourg (i.e. the percentage of judgments against them in which one or more findings of violation have been made between 1959 and 2011). I’ve also highlighted the UK rate in yellow, and the average of all judgments against all states in red.

As you can see, between 1959 and 2011, the Court handed down some 14,875 judgments, of which 12,425 found that at least one violation of the Convention had occurred: that’s 83.53% of all judgments given. The United Kingdom, by comparison, achieved a much more favourable level of success in its litigation. During the same period, the Court has made 462 judgments respecting the UK, of which 279 made at least one finding that the Convention had been violated: only 60.39% of judgments against the UK were adverse. Forty-two of the current forty seven member states lose a higher percentage of cases, from Ireland’s 62.96% upwards.

Of course, percentages can misleading. For example, the chart shows that Monaco, Montenegro and Liechtenstein have the highest rate of adverse judgments by the Court, with every case (100%) going against their governments. What this doesn’t show, however, is that the body of litigation generated by these three states is tiny – between them, they’ve generated only fourteen judgments in total. However, the same cannot be said for the litigation against Germany (234 judgements, 67.95% adverse), France (848, 73.94%), Italy (2,166, 76.22%), or Russia (1,212, 94.06%), all of which enjoy an (often substantially) higher rate of defeat in Strasbourg proceedings than the UK’s comparatively modest 60.39%.

Of course, critiques of the Court’s deliberations and conclusions may be qualitative as well as quantitative: one may object to the sorts of cases the Court decides, and the substance of its decisions, as well as the overall number of decisions made. One may be a nationalist, ideologically hostile to any erosion in state sovereignty, by whomever, for whatever purpose. That’s a fair legal and political game to play. What is a mischief, however, is pressing the factoid and the false impression into the service of that ideology. And in this respect, the dominating victim-fantasy of a judicially embattled Britain which now so powerfully grips the conservative UK press and politics is a fact-free zone.

This guest post is by Andrew Tickell, a doctoral Researcher at the Centre for Socio-Legal Studies, University of Oxford. You can find him on Twitter as@peatworrier

Sign up to free human rights updates by email, Facebook, Twitter or RSS

Related posts: